Discovery of the New Cohere Summarization Endpoint

Two weeks ago, Cohere.ai announced their new dedicated summarization endpoint!

For someone currently doing their PhD on text summarization, this is both worrying, but obviously also a rather intriguing development: while recent advancements have been focusing on rather broadly applicable models (think, chatGPT), providing more task-specific alternatives seems to be the niche that Cohere is carving out for themselves.

Adding to the surprise of seeing a dedicated summarization endpoint is the fact that text summarization is really hard; in the last 50 years, a lot of progress has been made, but our current state-of-the-art models still suffer from annoying problems such as correctly retaining factuality of the input text.

Another problem is the actual definition of “summaries” in different domains. Methods for generating a “good” summary of a news article are generally useless when it comes to generating the summary of a court ruling, or generating radiology reports from doctor notes.

Due to the combination of these (and other) factors, there are comparatively few productive settings in which summarization is actively used. To my knowledge, the two main applications using some form of summarization right now are some news aggregators, summarizing information from multiple news articles (which primarily uses extractive methods, meaning directly copying existing sentences from the input documents), as well as the recently introduced “Document TL;DR” generator in Google Docs (the latter using a variant of their own PEGASUS neural model).

This lack of tooling and remaining issues also means that companies (read: “paying customers”) are relatively unlikely to employ summarization systems or plan task settings where they would be directly used. While the imagined benefits of summarization systems are high, the current risks associated with their usage and the practical issues arising from their usage still outweigh these benefits. However, the fact that Cohere has a free tier available, as well as their claim of having a broadly applicable endpoint, makes it drastically more available to not only customers, but also the associated research community (and other folks keen on exploring AI-based tooling). To get a first feel of the new offering, I took the API for a spin, and want to put this new endpoint into the context of currently ongoing research.

What we know about their model

The blog post announcing the feature gives about as much detail as one can hope from a company: Opening with an accurate and concise system-generated TL;DR, the article then goes on to talk about some of the basic properties available.

To me, the most interesting fact is the unusually long context available for this model (50,000 characters max).

To put this length into context, we can compare it to the usually employed unit of “subword tokens”. These are vaguely similar to syllables, meaning a word can be broken down into individual sub-parts, to cut down on the required vocabulary for any collection of texts (note that this is a very generic simplification of the topic and should not be taken at face value; in fact, most subwords specifically do not correspond to actual syllables).

Assuming a mean subword token length of about 6 characters (based on some basic back-of-the-envelope math on top of bert-base-uncased model’s vocabulary file), the popular 512 subword limit of most transformer models comes to about ~3,100 characters in length for comparison.

Extrapolating to around 50,000 characters puts this in the ballpark range of 8,192 subword units of context length, which is on the extremely high end of contexts considered in recent research.

However, a key detail about the model is hidden further down in the article:

“[…]We extract key sentences from the document up to the context length, and then generate a synthetic document composed of the combination of those key sentences.”

Hybrid Summarization to the rescue!

This is a strong indicator that Cohere makes use of a joint architecture which is known as a hybrid summarization system, and is a popular trick to circumvent the general length limitations of transformer models. As described in the quote, the first part of a hybrid summarization pipeline consists of a “selector” method, which will highlight and extract a number of segments (usually sentences) in the original document. In research, this is also called an “extractive” summarization system, and will ensure that any text part is guaranteed to appear in the input document, which makes generation both cheaper and faster. Ultimately, this first stage is therefore used to drastically cut down the context length, without sacrificing too much loss in relevant content for the final summary at this stage.

Only during the subsequent stage, a larger (and more expensive) language model is then run to actually generate what we call an “abstractive” system, i.e., generated text does not necessarily appear in the original input, and can constitute a re-write of segments (or, more worryingly, can be made up completely).

Importantly, this use of preliminary selectors, which are often comparatively cheap approaches, drastically improve the computational efficiency of the entire pipeline compared to a “direct” approach, such as feeding an input text directly into a GPT-like model.

A likely extractor

There are of course different ways in which the pre-selection can be done, and nothing more is said in the article itself. Without further information, we can speculate on the specific details based on popular extractive models (which constitute the first part of the pipeline).

Given the input length limitations, it is unlikely that Cohere is employing an extractive model which is performing extractive summarization with Transformers, e.g., PreSumm or similar libraries. This is based primarily on the fact that the length limitations are also applicable in extractive settings. Furthermore, utilizing a supervised extractive model requires additional training data on “segment relevance” (i.e., judging which sentences are to be extracted); this again is highly dependent on the text’s domain and potentially limiting the generalizing qualities of such a system.

In my opinion more likely is a pipeline employing an unsupervised approach. Here, no specific training data is required, and oftentimes these methods have a decent performance across different domains.

One very likely approach is the combination of LexRank, a tried-and-tested method from 2004, augmented with modern sentence embeddings. This use case is even suggested by Nils Reimers, himself Director of Machine Learning at Cohere.

Especially with Cohere providing dedicated (multilingual) embedding endpoints, this is also a neat way to integrate several of their endpoints in one go.

Finally, it can be argued that unsupervised approaches also provide a more reasonable cost for inference, depending on their use of neural architectures internally. However, using embeddings generated with neural models kind of defeats any argument on performance, so this is no certainty.

Details on the abstractive part

Based on further parameters available, there seems to be good reason to assume that the abstractive model is largely based on Cohere’s existing .generate() architecture, with some additional fine-tuning towards specific summarization tasks.

We can assume that some labeled training data was obtained to learn the distinction of different output styles (paragraph vs bullets) and extractiveness (note that this parameter is not available in the Beta playground endpoint, but rather only mentioned in the docs).

I have tried to extract portions of the used prompt, however, it seems that Cohere has sufficient query blockers in place to prevent a “quick investigation” from my side, at least.

Based on the “additional command” parameter, it seems that a model following the instruction-fine-tuning paradigm was already used for this purpose, which would make this more similar to Cohere’s “command-xlarge-nightly” model than the older (more generic) “xlarge” variant.

Testing the waters

With the speculations about implementation details out of the way, we can now actually take a look at the systems and some preliminary outputs tested by yours truly. Note that this is still a rather anecdotal evaluation on a fairly small (but diverse) document set and a more thorough investigation is planned for the future.

In particular, I have a few general points that I look out for when interacting with summarization systems and that I will also focus on in this preliminary investigation:

- Are they capable of retaining factuality between the input and the summary?

- What part of the text is relevant information extracted from? Are relevant sentences clustered around the beginning, or actually appearing later in the text?

- How does the model perform for texts from different domains (legal, financial texts)?

- How well does the system perform for texts that are not in English?

- Are there any other non-grammatical outputs, such as repetitions or otherwise incoherent segments?

- As a secondary focus, what is the inference time of the model?

The “dataset”

I wanted to cover some fairly diverse settings, which at the same time have some relation to my own research (primarily non-English summarization and long-form summarization). These were the documents I have experimented with:

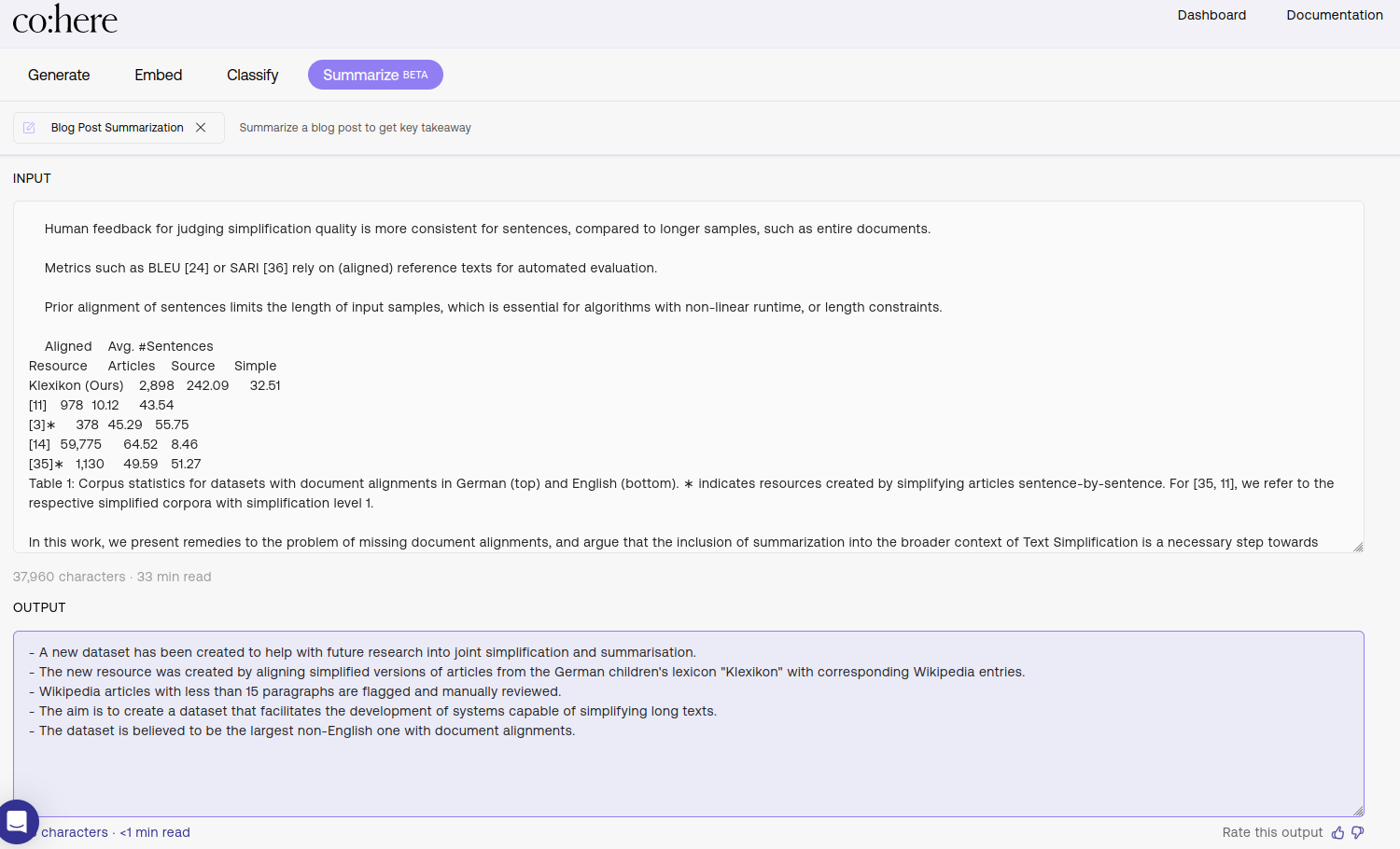

- One of my own papers, since I can fairly accurately judge the accuracy of the resulting summary without having to read the entire document. For conversion, I rendered it with arxiv-vanity and manually removed the abstract from the document to encourage sentence selection from portions not at the beginning.

- A mail conversation I had with a colleague about a technical topic. This rather long thread is in German, which further makes this an interesting sample document of cross-lingual summarization, in addition to also being fairly difficult as a “turn-based” conversation.

- A news article from today’s list of articles on cnn.com, to avoid news articles already present in the training corpus. I particularly picked one where the information is rather well-distributed across the article, and not just present in the first few sentences again.

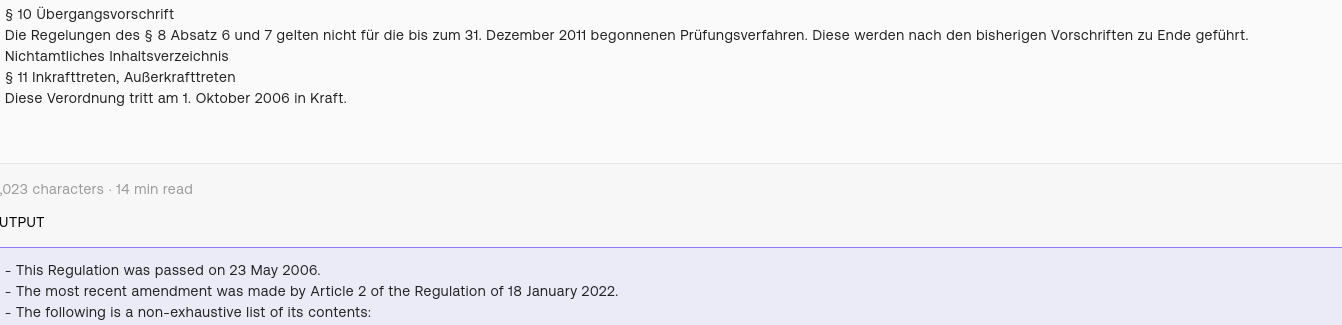

- A (fairly short) German law book. I used the “Verordnung über das Meisterprüfungsberufsbild und über die Prüfungsanforderungen in den Teilen I und II der Meisterprüfung im Dachdecker-Handwerk (Dachdeckermeisterverordnung - DachdMstrV)” (a law about obtaining an advanced associate’s degree for the roofer trade) don’t ask me why this one, it was the first one I clicked.

A quick note on the reproducibility: The temperature setting for all my experiments was between 0.0 and 0.8, which is fairly low. Even so, with non-zero temperature, the reproducibility of results is not guaranteed. This means that my insights (despite attempts with repeated “sampling”) may not be always the same. Please bear this in mind!

Result Summary

“Recursive Summarization”: Summarizing my own work on summarization with the Cohere endpoint.

“Recursive Summarization”: Summarizing my own work on summarization with the Cohere endpoint.

I’ll start with some interesting observations about the factuality of responses (1). Without generalizing from these results, I personally had much more success in obtaining consistent answers when going for generation in the “bullets” format over coherently written “paragraphs”.

Especially the paragraphs format was extremely sensitive to the generation temperature, and even with fairly low values (0.3) I sometimes got completely unfounded facts (e.g., that my dataset was created by researchers at the “Max Planck Institute for Psycholingustics”, despite me being at Heidelberg University").

Otherwise, especially for news-like articles, the consistency was surprisingly good, even if some references where incorrectly attributed in the German-to-English setting.

Instance of a factually incorrect statement. The law goes into effect on the 1st October, 2006 (last sentence in the German text); the stated date (23rd May 2006) is mentioned as the document creation date at the very beginning of the article.

Instance of a factually incorrect statement. The law goes into effect on the 1st October, 2006 (last sentence in the German text); the stated date (23rd May 2006) is mentioned as the document creation date at the very beginning of the article.

Regarding the multilinguality (4), I can happily report that it works to some extent; the endpoint is capable of “processing” German articles, but even with explicit prompts being added, will only respond in English. This is still a significant step-up, but probably not entirely useful for customers looking into summarizing documents in other languages. Translations were in my understanding pretty much always accurate; some fluency issues could be observed in the translation of the German law text, but I would argue that I myself could not have done a better job, either.

Similarly, fluency or repetitions have not been an issue at all (5). In none of the tested scenarios did I encounter output text that was plain “ungrammatical”. I am not sure if Cohere employs output post-processing steps, such as n-gram blocking or similar, but it seems that the RLHF-trained models (i.e., most instruction fine-tuned models right now) have less problems with that anyways.

For longer input texts, I noticed that the system was focusing a lot on what appears to be (sub-)headings of the texts, or otherwise shorter segments; this has happened to me when utilizing embedding-based extractive methods (such as the modified LexRank approach mentioned before), which are generally suited better for shorter segments. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but requires careful pre-processing by users for instances where the actual document body is more relevant than heading text.

The only problem regarding the sentence selection (2) was for the mail thread. While the output text accurately summarized the individual turns (e.g., individual responses without focusing on previous parts overly much), it failed to account for the “reading direction” of pasted mail inputs. Instead of reading “bottom-to-top”, as with most mail interactions, the system interpreted the reading direction as “top-to-bottom”, which inherently caused the summary to be inverted.

The mail setting was also the example where it was the easiest to identify that sentences were not just chosen from the beginning, precisely because it did indeed focus on multiple different responses within the mail thread. The one negative thing about the mail summaries where the almost overly short summaries, even when setting to the longest output format. A particular variation in sentence length could be observed as well.

For other articles, it was a bit harder to tell where content was chosen from, especially for news-related documents (where important mentions are expected in the beginning, anyways). However, even in my own paper, it would refer to mentions that appeared well within the document body.

This is a pretty decent indicator that it also works well in domains (3) where the input is less uniform than a news article. I wasn’t able to test it with medical documents (partially because I also lack domain knowledge), but for the legal use case it performed somewhat okay.

A final word in the inference times (6): I would say that currently the model is prohibitively slow for any text >10,000 characters, unless latency is not an issue (e.g., for pre-computed summaries). For the paper, processing time went on for around 4-6 seconds (estimated), but shorter texts were obviously much faster. I’m also not sure if there are added benefits of using the non-free tier for inference latencies, but I don’t think there are.

What’s next?

This poses a question to which we certainly have a less clear picture right now.

In my opinion, there are several ways which are logical and immediate follow-ups on the existing model endpoint.

I expect that they will expand the examples and documentation website. Currently, linked pages in their docs about summarization still refer to the general-purpose generation endpoint (see, “Build a summarizaiton app” in the bottom left), which is precisely not the one to use for this task.

Secondly, explicit training for multilingual summary experiences could be a possible extension. The model already exhibits a (albeit weak) multilingual tendency, which allows users to explore foreign-to-English summarization settings. If Cohere manages to extend their functionality to some of the other languages with a potential customer base, this could be a realistic extension.

Something that will also likely be expanded is the degree of customization possible. While the (beta) endpoint already includes generic parameters such as “length”, “extractiveness” and a mild form of styling (“bullets” or “paragraphs” being the available choices), recent trends in summarization research have shifted to a much broader degree of “controllable generation”. Similar directions can be observed in the “more general LLM research”, where instruction-tuned tooling is strongly preferred by users over more generic LLMs.

While there is also an option to give user-specified free-form instructions is already in place, it currently does not seem to affect the produced output too much. If Cohere manages to expand on the customization options available this way, a much more generic set of “summarization-like” tasks could be approached. This includes, for example, writing entity-centric summaries, where the summary provides a much more targeted text compared to a (broader) input document, or data-to-text settings, which is highly relevant in financial/business settings.

However, more important will be the degree of adoption by clients; I suspect that we will see the emergence of more tailored endpoints in the near future, which specifically cater to the needs of different specialized domains, again, possibly for specific legal/financial/medical documents. Here, a much stricter focus on factuality is generally required, and if useful application scenarios can be identified, it requires the adoption of slightly more consistent summary generation than currently possible. I am not fully convinced at this point that the “extractiveness” parameter delivers the required level of factual accuracy, yet. I also have a particular pet-peeve with the “randomness” introduced by the temperature parameter in general, as it prevents reproducible outputs at all, it seems. If users are interested in consistent answers, then the bullets-style format seems to be the more reliable choice.

In summary (no pun intended), it seems that Cohere has not released a major groundbreaking leap forward at the scale of chatGPT – but they might not have to. Providing a highly usable experience to a smaller set of dedicated users can pay off for them in the long run; a concise feature set with real application value to users will ultimately beat the comparatively flashy but less straightforward chatGPT. As for myself, I am currently evaluating the model on a broader dataset for performance on academically used evaluation metrics; so stay tuned for a part two!

PS: This post’s title image was taken in UBC’s beautiful Botanical Garden, which I visited just before starting my exchange year in Toronto in August 2017.